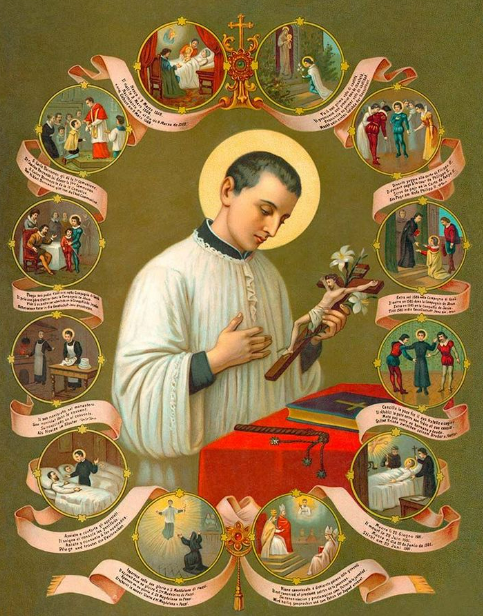

Saint Aloysius Gonzaga: His Purity, Candor, Penance and Mortification

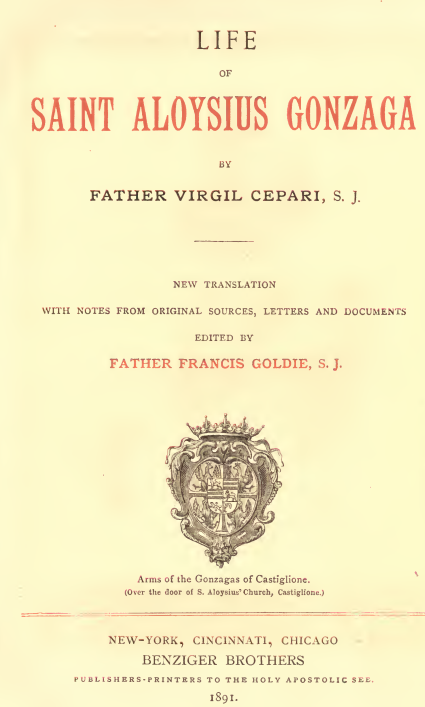

This 10-point review of quotes from “Life of Saint Aloysius Gonzaga” (1605) by Fr. Virgilio Cepari, SJ, highlights the saint’s virtues, purity, and penance. Written over 400 years ago, it still impacts us today, offering profound insights into his character and how he sought after Christian perfection.

10 Amazing Facts for the Soul

St. Aloysius: His Purity, Candor, Penances, and Mortifications

1

Purity of St. Aloysius

Maintained Virginity in Soul and Body

“He always preserved the precious gift of virginity in soul and body in all the perfection that has been related.”

Saint Aloysius stayed pure in both his thoughts and actions, keeping himself completely devoted to his faith and principles.

2

Candor of St. Aloysius

Always Spoke Truthfully and Openly

“In his speech and conversation, he was perfectly truthful and straightforward, full of openness and frankness.”

Saint Aloysius always spoke honestly and clearly. He didn’t hide his true thoughts or feelings, making him a very genuine person.

3

Genuine & Authentic

Meant Exactly What He Said

“Everyone knew that ‘yes’ with him meant ‘yes,’ and ‘no’ meant ‘no,’ without any fear of equivocation or deceit.”

When Saint Aloysius said something, people could trust that he meant exactly what he said. He didn’t lie or try to mislead anyone.

4

No Guile

Believed Honesty is Essential for Society

“He used to say that the duplicity, dissimulation, deceit, and equivocations so common in word and deed in the world are the ruin of human society, and in religion, the poison of religious simplicity and the pest of the young.”

Saint Aloysius believed that dishonesty and trickery are very harmful to society and especially damaging to religious life and young people.

5

Penitential

Strong Dedication to Physical Penances

“As for mortification, so great was the inclination of Saint Aloysius for bodily penances, that if his superiors had not restrained him, he might easily have shortened his life, for his fervor carried him beyond his strength.”

Saint Aloysius was so committed to doing physical penances (sacrifices) that he would have harmed his health if his leaders hadn’t stopped him. He was very passionate and dedicated.

6

Obedient & Trusting in Superiors

Trusted Superiors with Penance Decisions

“He knew his want of bodily health, and yet felt urged interiorly to practices of penance, it seemed to him that his superior, who knew everything, would only allow him what it was God’s will that he should do, and would refuse all the rest.”

Even though Saint Aloysius knew he wasn’t very strong, he still felt a strong inner drive to do penances. He trusted that his leaders would only let him do what was right and stop him from overdoing it.

7

Penance or Perish (St. Luke 13:3)

Believed Penances Improved His Character

“He was a crooked piece of iron and had entered religious life to be straightened with the hammer of mortification and penance.”

Saint Aloysius thought of himself as needing improvement and believed that doing penances would help make him a better person, just like hammering can straighten iron.

8

Spiritual Reading & Eucharistic Adoration

Did Spiritual Work When Penance Denied

“When his superior refused some penance to Saint Aloysius, he endeavored to make up for it by some other spiritual work, reading a chapter of Thomas à Kempis, or visiting the Blessed Sacrament.”

If Saint Aloysius wasn’t allowed to do a certain penance, he would instead do other religious activities, like reading spiritual books or praying.

9

Sanctifying Every Present Moment

Practiced Mortification in All Activities

“Whether he was standing, walking, or sitting he always found some means of practicing mortification.”

No matter what he was doing, Saint Aloysius always found ways to practice self-discipline and make sacrifices for his faith.

10

Public Humiliations

Wanted Public Reprimands to Improve

“He had a great desire to be publicly reprimanded, and gave his superiors a list of his defects for this purpose, but as he found that what he noted as defects were considered virtues, and that he received praise instead of blame, he resolved not to ask again for such rebukes, as he found them rather a loss than a gain.”

Saint Aloysius wanted to be corrected in public to help him improve. He listed his faults for his leaders, but they saw these as good qualities and praised him instead. So, he decided not to ask for public corrections anymore, as it didn’t help him as he had hoped.

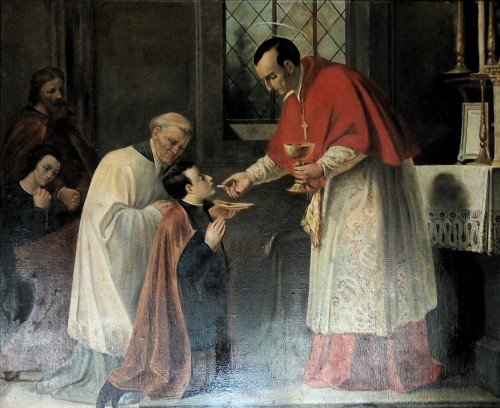

Can You Find Saint Aloysius Looking at YOU?

Triumph of St. Ignatius ceiling fresco

The image in the header at the top of this page is from the ceiling of the Church of St. Ignatius in Rome, where the remains of Saint Aloysius Gonzaga are kept. Check it out to see if you find St. Aloysius “up in heaven” looking down on you.

For More Information visit the website

Chapter XVI: His Purity and Candor, His Penances and Mortifications

Regarding the chastity of Saint Aloysius, we need only say that he always preserved the precious gift of virginity in soul and body in all the perfection that has been related in the 2nd Chapter of Part I. In his speech and conversation, he was perfectly truthful and straightforward, full of openness and frankness. Everyone knew that “yes” with him meant “yes,” and “no” meant “no,” without any fear of equivocation or deceit. He used to say that the duplicity, dissimulation, deceit, and equivocations so common in word and deed in the world are the ruin of human society, and in religion, the poison of religious simplicity and the pest of the young: and that such defects never could exist with the true religious spirit.

As for mortification, so great was the inclination of Saint Aloysius for bodily penances, that if his superiors had not restrained him, he might easily have shortened his life, for his fervor carried him beyond his strength. To some who seemed to wonder that he had no scruple of asking leave so incessantly for penances, considering his weak health, he would answer that as he knew his want of bodily health, and yet felt urged interiorly to practices of penance, it seemed to him that his superior, who knew everything, would only allow him what it was God’s will that he should do, and would refuse all the rest.

The Saint added that sometimes he made requests which he knew would not be granted: for as he could not do all he desired, he wished at least to offer this his desire to God and to make a proposal to his superiors, which could not fail in many ways to be of gain to him, on many counts. Sometimes it would be a cause of humiliation, as others would be astonished that he could ask for such things, and so conclude that he did not, in this matter, know himself. It was sometimes God’s will, however, that things should be allowed him which amazed everybody.

Someone asked him one day very seriously how it was possible that possessing good judgment, he should despise the advice of so many holy and wise Fathers, who had often exhorted him to lay aside the great severity of his penances and the intense attention of his mind to spiritual things. Saint Aloysius answered: “Two kinds of persons give me this advice: of them, some lead so holy and perfect a life, that I see in them nothing but what is deserving of imitation, and often it occurs to me that I will follow their advice; but as I afterwards notice that they do not follow that advice in their own regard, I have judged it better to follow their example than the counsel which they give me through charity and compassion. There are others who themselves practice the advice which they give me, and are not devoted to these penances: but I prefer to follow the example of the first, rather than the advice of the second.” Another reason he gave was that he had great doubt that nature, without the practice of mortification and penance, could long continue in a good state, but that by degrees it would fall back into its old condition and lose the habit of suffering acquired in so many years.

Saint Aloysius used to tell me and others that he was a crooked piece of iron and had entered religious life to be straightened with the hammer of mortification and penance. When he heard others say that perfection consists in the interior, and that the will, rather than the body, must be scourged, he would reply: “Do the one without omitting the other”; for the two must be united, as has always been the practice of the ancient saints and the first Fathers of our Society. Our holy Father, Saint Ignatius, as we read in his Life, was greatly given to penance and treated his body with much severity. And in the Constitutions, he has left on record that there are no fixed watchings, fasts, disciplines, prayers, or penances prescribed to the professed or graduates of the Society because it is supposed that they will be so perfect and so given to these things, that they should require the bridle rather than the spur, whenever they know that bodily penances do not interfere with the holy actions of the soul.

The time for these penances, he added, is when we are young and strong; for with old age come infirmities which prevent us from performing them. The saints towards the end of their lives, and when old, lessened their corporal penances in proportion as they were so much more given to exercises of the mind, though they never entirely omitted them.

When his superior refused some penance to Saint Aloysius, he endeavored to make up for it by some other spiritual work, reading a chapter of Thomas à Kempis, or visiting the Blessed Sacrament. Whether he was standing, walking, or sitting he always found some means of practicing mortification. When hair-shirts, disciplines, and extraordinary fasts were forbidden him, he tried to find out penances to which his superiors would not object and which could not hurt him, as for instance to give the Tones, practice in preaching which is made before the others, in Spanish, imagining that this would make everyone play the fool with him, and this was granted.

Enough has been said of his penances, which he so highly valued, and employed with so little regard to his health, that some said they feared he would have some scruple at the hour of death for treating his body so ill, and that he might have to do penance in purgatory for his indiscretion. To this he gave an answer in his last sickness, which will be recorded in its proper place.

He did not need to mortify his passions very diligently, for he had done it already so thoroughly, that he seemed to be without any passions at all. But Saint Aloysius used diligence in examining all that passed in his soul, and when he found that he had committed any fault, he did not grieve about it too much, but at once humbled himself before God and begged pardon from the Divine Mercy, resolving to confess it, and then troubled himself about it no more. This method he had learned from his Master of Novices, who used to say that when we sin, the best remedy and that most pleasing to God and hateful to the devil, is to humble ourselves at once before God, and then raising our heart to Him, to say: “O Lord, you see how weak and miserable I am, and how easily I fall. Pardon me, O Lord, and grant me grace not to slip again”; and after having made an act of that kind to remain tranquil.

This was the practice of Saint Aloysius, who used to say, to grieve excessively may be a sign of a want of self-knowledge, for he who knows himself is aware that his garden is fruitful in weeds and thorns. His great care was to find out the origin of his thoughts and desires, in order to see if there was any fault therein, and he toiled until he found out the truth so as to be able to confess it. His confessions were clear, brief and without scruples. His confessor, Father Robert Bellarmine, related of the Saint that he could say with as much clearness and distinctness how far a thought, desire or action had gone, as if he had seen it with his bodily eyes, so great was his interior light and self-knowledge.

He had a great desire to be publicly reprimanded, and gave his superiors a list of his defects for this purpose, but as he found that what he noted as defects were considered virtues, and that he received praise instead of blame, he resolved not to ask again for such rebukes, as he found them rather a loss than a gain.